Meditations on Lee Kuan Yew's Early Years

My attempt at understanding LKY through his words.

The Impossibility of Unscrambling An Egg

In 1998, Lee Kuan Yew published his memoir The Singapore Story as an attempt to remind a younger generation of Singaporeans how vulnerable Singapore truly was.

Singaporeans were born into stability, prosperity and comfort for the first time in our young nation's history. He was worried that Singaporeans would become overconfident and, thus, permanently lose their place in the world.

Once you scramble an egg, you can never unscramble it.

There is a Chinese idiom that goes - “ 富不过三代”. It means wealth does not survive three generations.

Why?

The first generation suffers great hardship in creating wealth. The second generation, although without the lived experience of suffering, hears from the previous generation. The third generation, accustomed to luxuries, takes their privileges as birthright and thus squanders the family's wealth in their lifetime.

We see this motif recur across history- be it Ibn Khaldun's Muqaddimah exploring the cyclical history of the pre-modern Islamic world or in Michael Hopf's infamous quote - "Hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, good times create weak men, and weak men create hard times."

The only way to break this pattern is to internalise the history of your forebears.

Millennials (like myself) and Gen-Zs who have never experienced LKY's leadership and have only learned of his contributions through textbooks are now forming a substantial portion of the population.

Most of us have a low-resolution understanding of his contributions to Singapore. LKY and his first generation of leaders feel too far removed and detached from where we stand.

Unfortunately, many of us are afflicted with hindsight bias, which leads us to assume that whatever success we have is preordained and whatever unpalatable policy must be removed.

We make a crude caricature of him, and depending on our politics, we either worship or abhor him. Worse still, we forget him.

But I thought it wise to consider Chesterton's Fence.

GK Chesterton, the famous British theologian, advocated that one should never destroy a fence, change a rule, or disregard a tradition until one understands its purpose.

I wanted to understand the stories he wanted to etch into the minds of every Singaporean, what drove him, what he feared, and what he thought was crucial for Singapore's continued existence.

I spent hours reading his memoirs, taking copious notes, and trying to see things from his perspective.

These are my meditations on The Singapore Story.

LKY's Childhood - A Huge Ripple

For want of a nail the shoe was lost,

for want of a shoe the horse was lost;

and for want of a horse the rider was lost;

being overtaken and slain by the enemy,

all for want of care about a horse-shoe nail

-Benjamin Franklin, The Way To Wealth

When I read about LKY's early childhood, I can't help but think about The Butterfly Effect.

I suspect that it's because one has so little control over one's life in childhood, yet it is a person's most formative period.

Things happen to you.

But, you can't make things happen.

LKY had enough good things happen to him in his early years to accelerate his journey to future success.

LKY was born into a sufficiently affluent family in colonial Singapore. His grandfather, Lee Hoon Leong who became business partners with Singapore's Sugar King, Oei Tiong Ham, who even after losing much of his fortune due to The Great Depression could still live in comfort and style.

At this time, most of the Chinese in Singapore were illiterate, and living in poverty. Many of them were coolies, general workers and street hawkers.

LKY's family was rich enough to give him a leisurely childhood and a quality education. But poor enough not to indulge him.

He recounted, "We were not poor, but we had no great abundance of toys, and there were no televisions. So we had to be resourceful and use our imagination. We read, and this was good for our literacy.."

LKY's English education, starting from Telok Kurau English School, which paved the way for his subsequent entry into Raffles College and then Cambridge, was very much dependent on his grandmother's blessings.

Originally, he was meant to study at a Chinese school. But, being a Peranakan, he struggled mightily. A young LKY pleaded for transfers on several occasions through his mother to no avail. Thanks to his mother's persistence, his grandmother relented.

Had she insisted on educating LKY in the same Chinese school, how likely was it that LKY would have the basic ingredients needed to become the brilliant lawyer and masterful orator he would become later in life?

During the Japanese Occupation, we would see LKY almost lose his life.

On a routine walk home, a soldier manning the gantry asked him to join a lorry full of young Chinese men.

He sensed something was amiss and asked permission to collect his belongings first.

Instead of returning, Lee Kuan Yew hid with his rickshaw puller, who happened to live at the checkpoint.

When a different soldier was on duty, he was cleared to leave.

Every Chinese man on that lorry was executed as part of Sook Ching.

Had Lee Kuan Yew complied, he would have died. Had the Japanese soldier rejected his request, he would have died. Had his rickshaw puller lived in a different place, he would have died.

This chapter of his early life drives home one point- luck is not trivial.

The Power of High Agency

At the same time, luck is what you make the most of it.

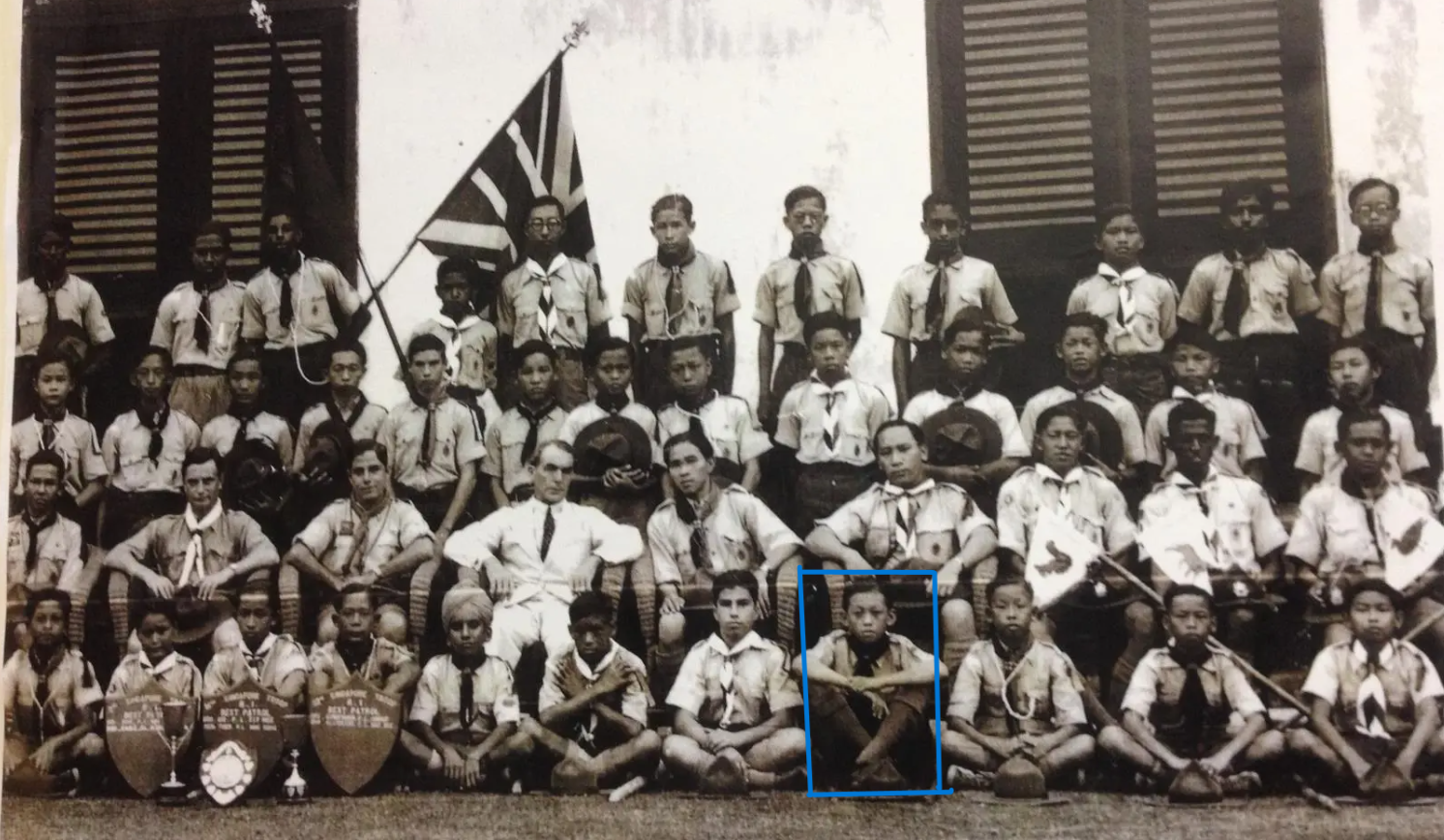

As subjects of the British colony, Singapore had the benefits of colleges and scholarships reserved for its brightest students. The cream of the crop could earn the Queen's Scholarship which fully sponsored them to study in the UK's best universities. LKY knew he had to do his best to come out on top.

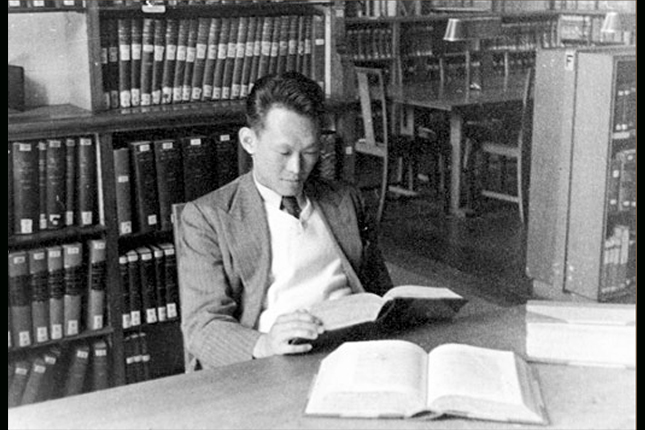

In his words, "I had set my heart on distinguishing myself in the Senior Cambridge Examinations, and I was happy when the results in early 1940 showed I had come first in school, and first among all students in Singapore and Malaya."

Throughout his time as a student, he studied hard. He almost topped the cohort in everything he took, only losing out to a certain Miss Kwa in English and Economics.

(This Miss Kwa was later known to be Mrs Lee Kuan Yew)

Here we get an early glimpse of LKY's relentless drive for excellence. When the parameters for success are clear, it pays to be relentless. But, when reality is murkier, being relentless is not enough.

In his 2009 essay, Paul Graham wrote that the essence of a good startup founder can be condensed into two words: relentlessly resourceful.

He elaborates, " In any interesting domain, the difficulties will be novel. Which means you can't simply plow through them, because you don't know initially how hard they are; you don't know whether you're about to plow through a block of foam or granite. So you have to be resourceful. You have to keep trying new things."

A relentlessly resourceful person does not let the world have its way with them. They are actively trying to shape the world.

Be it brokering the black market and starting a gum-making business during the war years, or learning Chinese to understand the warnings issued by the Japanese. This relentless resourcefulness is something I detected in LKY as he recounted his early years.

My favourite story has to be how he engineered a spot for his lover, Miss Kwa to matriculate a year early. Although she had secured the Queen's Scholarship in July 1947, the Colonial Office said they could only find a place for her in the next year.

Anyone else would have resigned to their fate. LKY got to work.

He navigated the complicated back office of Cambridge, speaking to clerks for introductions to deans of colleges. He passionately pleaded his case for Miss Kwa, arguing that she was a brighter student than he was and she was willing to study harder to attend college in time.

Girton College, a women's college, took LKY seriously and gave Miss Kwa a slot.

By October 1947, three months after Miss Kwa was told to delay her studies for a year, she had reunited with LKY.

It is this same relentless resourcefulness that would characterize his years to come as our Prime Minister.

The Japanese Interregnum : A Radical Reset

Between being loved and being feared, I have always believed Machiavelli was right. If nobody is afraid of me, I’m meaningless.

-Lee Kuan Yew

LKY saw those three years of Japanese occupation as the most important years in his life.

All his assumptions of how the world ran were destroyed when World War II broke out in Southeast Asia. During this period, LKY fully understood the idea of "power as the vehicle for revolutionary change."

It was those who wielded power that could shape a new social order, prescribe what was right and wrong and ultimately, dictate the fate of a population.

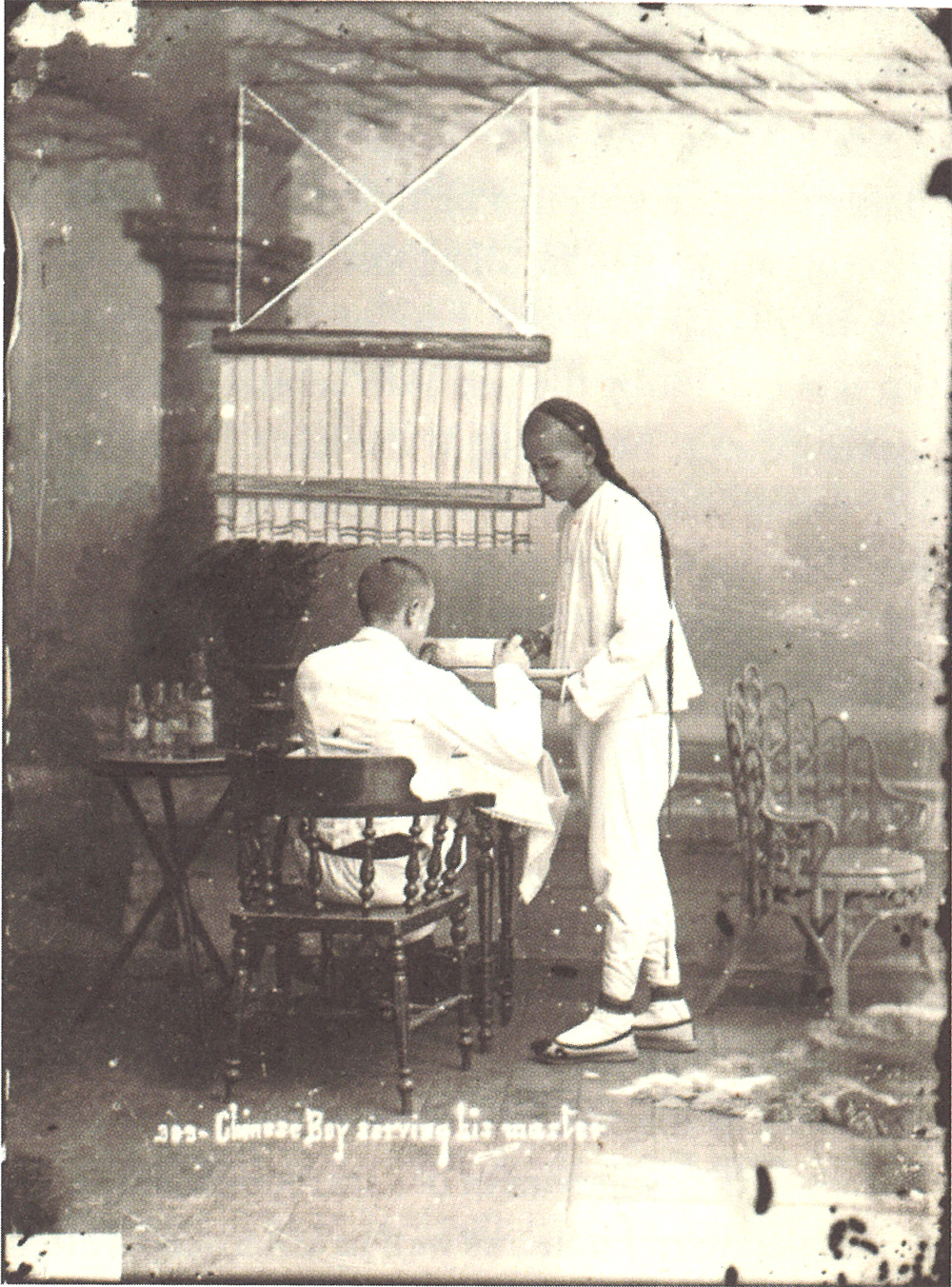

In the early 1900s, it was taken for granted that the British was simply a superior civilization and the white man, was simply a superior race. It was futile to attempt supplanting the colonial order. After all, the sun never set on the British Empire.

As he puts it, "There was no question of any resentment. The superior status of the British in government and society was simply a fact of life."

This culture was so ingrained in the colonies that for the small number of Asians who could mix socially with their white bosses, accepted the condescension and inferior status to the whites 'with aplomb' because they felt that at least, they were superior to the other Asians.

When the Japanese crushed the British in their campaign, their myth of inherent superiority was convincingly dismantled. LKY recalled that once he was cycling past a line of military lorries, he saw some Australian soldiers there to assist the British military. When he asked them how close they were to the front, the soldiers simply offered to give LKY their weapons, conceding that the battle was lost.

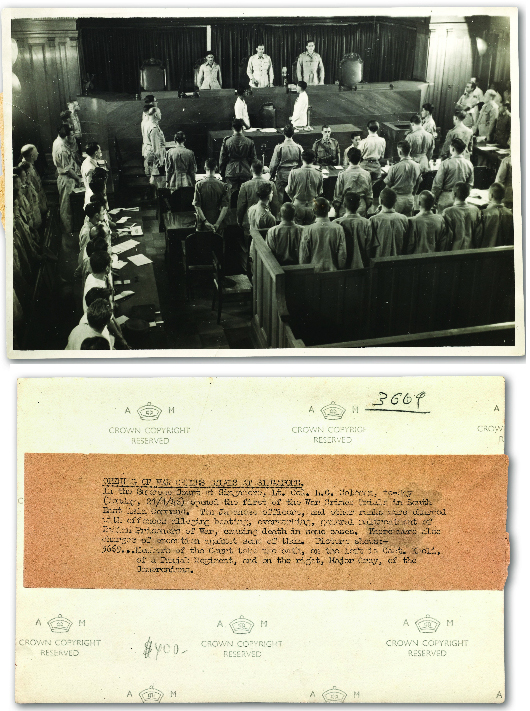

Yet, once the Japanese assumed power, all the talks of liberating their fellow Asians from the evils of colonialism were thrown out of the window. Now, the Japanese wanted to rule. They made decisions affecting life and death 'capriciously and casually' and ruled with a viciousness that LKY could never comprehend.

If you didn't bow to the soldiers correctly, you could be forced to kneel in the sun for hours or hold a heavy boulder till your arms gave way. If you were caught stealing, you could be beheaded. Then, there was the infamous Sook Ching, which saw the Japanese conduct genocidal killings of the Chinese population in Singapore.

(His colleague, Lim Kim San, who was detained for more than a month under the Japanese, provided a grim account of his experiences in 1944. Reading about his experience was nerve-wracking enough. If I was placed in the same situation as him, I am unsure if I could survive.)

This created so much fear in the general population that even when everyone was 'half-starved', crime rate remained amazingly low. The Japanese could demand obedience, and force the local population to' adjust to a long-term prospect of Japanese rule so that they had their children educated to fit the new systems, its language, its habit and its values, in order to be useful and make a living.' If the Japanese stayed on longer, LKY was sure that Singapore would have accepted the Japanese as our new masters "as part of the natural order of things"

When the war ended, liberation was bitter sweet. The locals who endured much of the suffering had no mechanisms to mete out justice. They had to depend on their colonial masters or the victorious Americans to punish the evil-doers. There was no complete squaring of the accounts. Many war criminals escaped punishment.

Even Yamashita, the commander-in-chief who signed off the directive to implement Sook Ching, was tried and hung by the Americans for the Manila massacre and war crimes committed in the Philippines without accounting for his approval of the senseless killing of Chinese men in Singapore.

Be it the British, Japanese or Americans, those in Singapore had to live with what the powers that be had decided for them.

They were powerless.

Through this horrific three-year episode, LKY learned the supreme importance of power. Any outsider who wanted to decide on Singapore's behalf would always act in their own self-interest, never Singapore's.

Thus, he concluded he had to wrest political power away from the British so that Singapore (or Malaya) could decide their own fate.

I found it interesting that during the Japanese Occupation, LKY internalized the value of fear in driving behavioural change. He stated that as a result of his life under the Japanese, he could "never believe anyone who advocated a soft approach to crime and punishment."

He would use the same playbook of harsh punishment to keep crime and corruption low. He would use fear to discourage 'uncivilized behaviour', punishing vandals, litterbugs and even people who urinate in lifts with hefty fines or even jail time.

His approach might not sound popular or politically correct today.

But, when I think from his point of view, compared to the casual attitude of the Japanese invaders towards life and death, abusing people at their whims and fancy, issuing a threat of corporal punishment for serious offences that can destabilise a nation you dedicated your life to building seem much more logical.

Making Sense of LKY's Early Years

When I read of LKY's early years, I can't help but feel lucky that I was born in an independent Singapore.

Imagine being born in 1900 in Singapore.

For 65 years, you will experience the pain of two world wars, decolonisation, race riots, a failed merger, and abrupt independence.

Only at the end of your life will you begin to enjoy the fruits of your labour.

What LKY's early years showed me was just how helpless Singapore was. No matter how gifted or hardworking you were, you could not sniff at a chance to achieve your ambitions. As a colonial subject, you had to kill your dreams. The best and brightest had to be content playing the master's servant.

At the same time, I saw the early makings of LKY. In the way he describes his childhood and youth, I see a person who is incredibly diligent, proactive, and adaptable. These traits would distinguish him as not just a formidable freedom fighter but a cerebral architect of national development.

To understand the genesis of LKY's worldview, you must read the early chapters of His Singapore Story.