The New China Playbook by Keyu Jin

Page Count: 306

Chapters : 10

Time Taken: 7.5 Hours

Keith’s Take

If you want to understand where China is heading towards, read this book.

(As China’s footprint in Southeast Asian economies increase (either via FDI or joint projects), I think this book is a must read for my fellow Southeast Asians.)

Critics say that she skirts or side-steps many political issues concerning China. But I feel that in many of these cases, they are nitpicking on her for not being critical enough on China.

I think she has done a great job of capturing the essence of Chinese policy preference, economic history and possible options that lay ahead.

Treat this book like a compass - it will give you a sufficient directional understanding of where China will head to.

Keith’s Notes

The Chinese Expectation of Government

What do citizens expect of their government?

If you are in the US, a Republican and Democrat will answer very differently.

In China, ‘citizens expect the government to take on large roles in social and economic issues and do not see interventions as infringement on liberty.’

The Conditions for China’s Model to Succeed

As China steps into its full potential, it cannot claim to be a superior alternative to the Western model of economic development (i.e Washington Consensus) until it fulfils the following two conditions:

- Escape the Middle-Income Trap (hitting >$30k per capita)

- ‘Demonstrate it can do a better job than free market economies of addressing the most intractable problems of capitalization and globalization’

The primary challenge as Prof Jin surmises, is that - it has developed

a system that is powerful in mobilization and executing big industrial pushes may not be as effective in fostering breakthrough technologies and sustainable growth vital to becoming a rich nation; one that is expedient when a nation and its people are singularly focused on economic growth does not necessarily have the resilience and flexibility to manage a much more complex and pluralistic society.

I noticed this in East Asian economies (particularly Singapore, where I hail from)—there is a general aversion to trumpeting one's own model because one is aware that it has 1000 caveats.

[As Robert Lucas puts it - “Simply advising a society to follow the Korean model is a little like advising an aspiring basketball player to follow the Michael Jordan model”]

China’s Economic Miracle

What explains China’s surge?

Prof Jin asserts, “China was catching up to its own potential. In this sense, it was not a miracle, per se”

The Soviet model failed and obscured the cultural fundamentals that helped China emerge as a great power in the past.

Among China’s cultural advantages were the contributions of Confucius (551–479 BC), the famous Chinese philosopher whose teachings emerged from his search for pragmatic solutions to the problems of his day.

She elaborates on how that has shaped much of the Chinese political psyche.

I summarise it here:

- Emphasis on Education and Meritocracy

- Frugality and Hard Work.

- Respect for Hierarchy and Authority

- Social Harmony and Stability

- Collectivism and the Greater Good

- Paternalistic Governance

- Ethical Leadership

These values shaped Chinese political thinking through its 2000 years of ups and downs, and this is what differentiated China from the rest of the developing economies.

Most never before reached an advanced level of institutional and economic development, or they were once prosperous economies that at some point succumbed to colonial rule.

In short, its “culture and history laid the foundations for China’s potential level of income, but the path to get there would require a radical overhaul of the economic system.”

The Deng Difference

I always wondered why LKY admired Deng Xiaoping so much.

My guess is that in Deng, he saw a masterful politician and leader. Deng could engineer his way back in from being a political outcast to becoming the Chairman.

At the same time, he could lead decisively to reform China.

Prof Jin confirms this,

Deng Xiaoping rose to the occasion by focusing on two issues. The first was creating party consensus by assessing Mao’s historical performance in order to avoid a long, drawn-out controversy over the Cultural Revolution; this would help unify the party rather than divide it… The second issue was how to implement new economic policies, and here Deng Xiaoping was both flexible and patient. Recognizing the dangers of uprooting China’s Soviet-style economy overnight through massive privatization programs, Deng took the approach of “crossing the river by groping for the stepping-stones.” This gradualism was an ingenious way of deferring some thorny issues, such as how private ownership could be reconciled with the ideals of a socialist state, or free exchange with Marxist theories of value.

How Reform Drove Chinese Growth

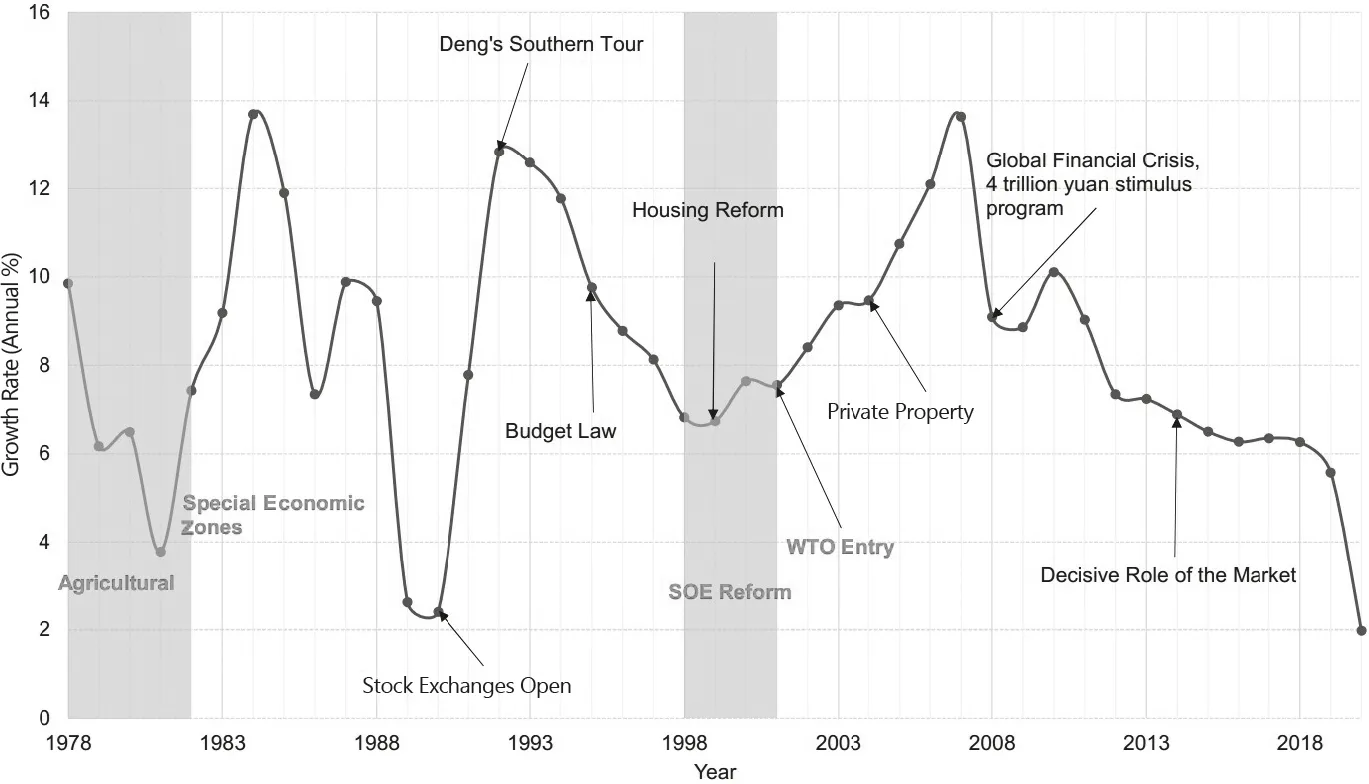

Reform is China’s second revolution,’’ Deng Xiaoping famously stated, and between 1978 and 2008 four major tides of reform triggered major surges of growth.

“Begin with an economy performing way below its potential; restore the link between effort and reward, releasing an avalanche of incentives, mobility, competition, price flexibility, and innovation; and open the economy up to experimentation with international trade and investment while maintaining political and social stability: now you have an economy primed for an explosive burst.

The CliffsNotes version of the four tides:

- Agricultural Reform (Late 1970s – Early 1980s):

- Household Responsibility System: This policy dismantled collective farming, allowing individual households to manage their own plots and sell surplus produce. This shift significantly increased agricultural productivity and rural incomes.

- Industrial Reform and Opening-Up (1980s – Early 1990s):

- Township and Village Enterprises (TVEs): Encouraging the growth of TVEs spurred rural industrialization and created employment opportunities outside the agricultural sector.

- Special Economic Zones (SEZs): Establishing SEZs attracted foreign investment and facilitated technology transfer, integrating China into the global economy.

- State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) Reform and Market Liberalization (1990s):

- SOE Restructuring: Reforming or closing inefficient SOEs aimed to enhance competitiveness and reduce fiscal burdens.

- Market Mechanisms: Introducing market-oriented policies, such as price liberalization and the development of financial markets, promoted a more efficient allocation of resources.

- Integration into the Global Economy (2000s – Present):

- World Trade Organization (WTO) Accession: Joining the WTO in 2001 opened global markets to Chinese goods and services, boosting exports and economic growth.

- Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Launched in 2013, the BRI aims to enhance global trade and stimulate economic growth across Asia and beyond through infrastructure investments

China’s Economic Malaise

From 1978 to 2008, China’s astounding growth rate brought huge costs.

Outside of pollution and corruption ,

Housing prices climbed at staggering double-digit growth rates, making housing less and less affordable to the average household. In the industrial sector, subsidies ran rampant, leading to oversupplies in steel, mining, and solar panels, to the point where some local officials suggested bombing the factories to cut back their supply.

What drove this?

The impatient desire of a nation to industrialise fast.

For a long period, the state’s mentality was that industrialisation was tantamount to modernisation and had to be China’s economic focus.

In an effort to grow as fast as possible, the interest rate was capped at an artificially low level. Cheap credit was everywhere.

Low interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing but hurt households striving to earn a decent return on their savings. This led to an economy with too little consumption, too much investment in the wrong places, and high net exports

Weaning China off steroidal industrial policies that feel good in the short run but are toxic in the long run is the key to sustained, high-quality growth and reconciliation of international disputes. The old model of growth must give way to a new model, one that is centered not on industrialization but on innovation and continued improvements in productivity.

In Singapore, we didn’t have the steroids of cheap credit. But we do need a new growth model.

The first generation of leaders were eager to get us out of poverty, we leaped from third world to first in one generation. They were able to mobilize the population in an unprecedented way.

For the first 40 years, state-led entrepreneurship drove growth and made Singapore an attractive destination.

But, if we want to pursue more innovation and greater improvements in productivity- we need a new playbook too.

The One Child Policy As The Great Natural Experiment

When China implemented the One Child Policy, it also conducted the world’s largest-scale natural experiment.

What makes the one-child policy in China so remarkable and potentially informative about the causal effects of fertility is that it was an exogenous event, something imposed by the government and not a matter of personal choice.

You could now compare one-child families to families with twins or triplets.

(It also helps that China’s population is 1 billion- which means its much easier to find twins in China than in Singapore)

In short, it helped us understand how fertility changes affect household behavior.

Of the many effects (including how it unintentionally advanced gender equality in China), the most interesting was the education arms race that emerged organically as a response to this policy.

On average they devote 25 percent of their annual spending to educating one child. This is an enormous sum. To put this in perspective, the average American household earmarks about 5 percent of its annual spending to educating one child. American families have more children, and differ from Chinese families in many ways, but the large discrepancy in per capita education spending suggests that the one-child policy significantly raised parental focus on education. The motive may be partly pragmatic—if we have only one child, let’s make sure that child is highly educated and can earn a higher wage to offset the lack of other children—or it may be driven by a desire to make sure our child can go further than the neighbor’s child.

Evolution of SOEs

The primary problem with SOEs is that they are treated like iron rice bowls. They are not there to maximize profit and are often inefficient.

Western thinkers would then argue that you should do away with them altogether so as to open up the market for greater competition and creative destruction.

China adopted a different route under Premier Zhu Rongji, who embraced “grasping the big and letting go of the small”; big SOEs were drastically overhauled, while smaller ones were left to sink or swim.

Major SOEs embarked on a period of fundamental restructuring, inviting strategic investors to take over a portion of equity, selling off minority interests to the public, or becoming listed on the domestic stock exchange. The result for state-owned firms was massive shrinkage.

The major SOEs would become more profitable and remain under state control. They would become world-conquering, global conglomerates.

As of 2022, half of Chinese SOEs continued to remain among the world's 500 largest companies.

This transformation also rendered obsolete the conventional wisdom that all-out privatization was the inevitable future for the command portion of China’s economy. The big bang approach of massive overnight privatization applied in Russia and Eastern European economies, with its oligarchy, corruption, and social problems, turned out not to be the only option. It seemed that China could successfully create a dual-track system where SOEs and the private sector could coexist, once the former was gradually reformed. This way, the messy transfer of assets from the state to an elite group of political moguls was averted, along with mass layoffs, high unemployment, and social instability.

I still think people take for granted the impressiveness of China's avoiding the Soviet fate. Even with all its structural problems, to transit from a command economy to a (relatively) free-market economy without huge social upheaval and still get a massive improvement in the standards of living for most Chinese is an impressive feat.

- A secondary side-effect of having SOEs is that they serve as a ‘role model’ for China's new waves of tech titans. The tech firms that made it big in China have responsibilities and duties reminiscent of the old SOEs, such as providing services and creating technologies to aid the government during the pandemic or pledging funds to help recover from natural disasters.

(This is in part because even these entrepreneurs recognize the important role the state plays in enabling their enterprise)

The Mayor Economy

The story of Singapore’s economic miracle would be incomplete without discussing its trade and FDI promotion agency, the Economic Development Board (EDB). It was instrumental in helping Singapore ‘terraform’ itself to suit investors’ needs and purposes.

In China, it’s the mayors who play this role.

Prof Jin cited the success story of Kunshan, which, trapped between Shanghai and Suzhou (with no way to compete for US and European FDI in the early days), decided to reinvent itself as a niche market for wealthy Taiwanese investors.

To do so, it initiated a wide range of business-friendly policies, including financial and fiscal support, land leases, one-stop license applications, and lower thresholds for capital. In addition, it adopted a tough no-tolerance policy on corruption. As a result, Taiwanese investors felt both sought after and safe.

(something not too far off from Singapore’s approach)

The reason why you have such entrepreneurial mayors is that they are often politically incentivized to achieve economic growth by scoring well on performance metrics like GDP growth in their evaluations and prospects for promotion.

However, this focus can lead to unintended consequences such as GDP worship, excess borrowing but most notably, corruption.

When development projects are up for grabs, there are many rent-seeking opportunities along the way: issuing licenses, channeling finances through local state banks, and auctioning land leases all offer local government officials many opportunities for profiteering. For some, the temptation to abuse the power and divert funds into private pockets can prove irresistible. Many of them think, If I’ve been so instrumental in growing the economic pie, why shouldn’t I have a slice?

In a small city-state like Singapore(as the S Iswaran case showed), it’s easy to spot and punish this kind of behaviour.

At the top, we only have 20 Cabinet Ministers. In China, you have 707(!) cities. Naturally, graft is hard to weed out.

Corruption has been a systemic dilemma since imperial China. Right now, under President Xi, China is on a huge anti-corruption drive, cracking down on officials abusing their power for personal gain.

Will that encourage or discourage policymakers from being more entrepreneurial? I am not too sure.

Why Chinese Equities Suck

Another paradox of the Chinese economy is that it has the best-performing economy but the worst stock market.

Pro Jin highlighted this key stat that broke my brain: there is zero correlation between Chinese stock performance and GDP growth rates.

That’s wild.

One key reason is that they chase profits to a fault.

I once spoke to a Chinese entrepreneur on a trip to Shanghai. He told me that in China, many firms will do whatever it takes to be profitable.

This sounds logical until I hear his explanation.

If profit maximisations is your sole North star, it doesn’t matter what your business is. You can be a real estate developer. And if the EV market gets hot one day, you better strike into it. Because you never know how much profit you can get. (This company is Evergrande)

Prof Jin backs him up in explaining why Chinese companies have such atrocious investment efficiency,

They make bad decisions!

Often this relates to the Chinese zest for bending rules. Firms lend money to other firms closely related to the controlling shareholder (a move known as “tunneling”). They go on spending sprees, buying up companies unrelated to their core business. After going public, a Chinese motorbike company that was once a household name went on to buy pharma companies, while an equally well-known pharma company started acquiring golf clubs, hotels, and car companies; they both tanked. After becoming one of the largest companies in the world, Evergrande, the real estate empire that became a debt bomb threatening China’s financial stability in late 2021, expanded into areas in which it had no expertise, including electric cars, soccer clubs, bottled water, and pig farming.

How China Innovation Works (For Now)

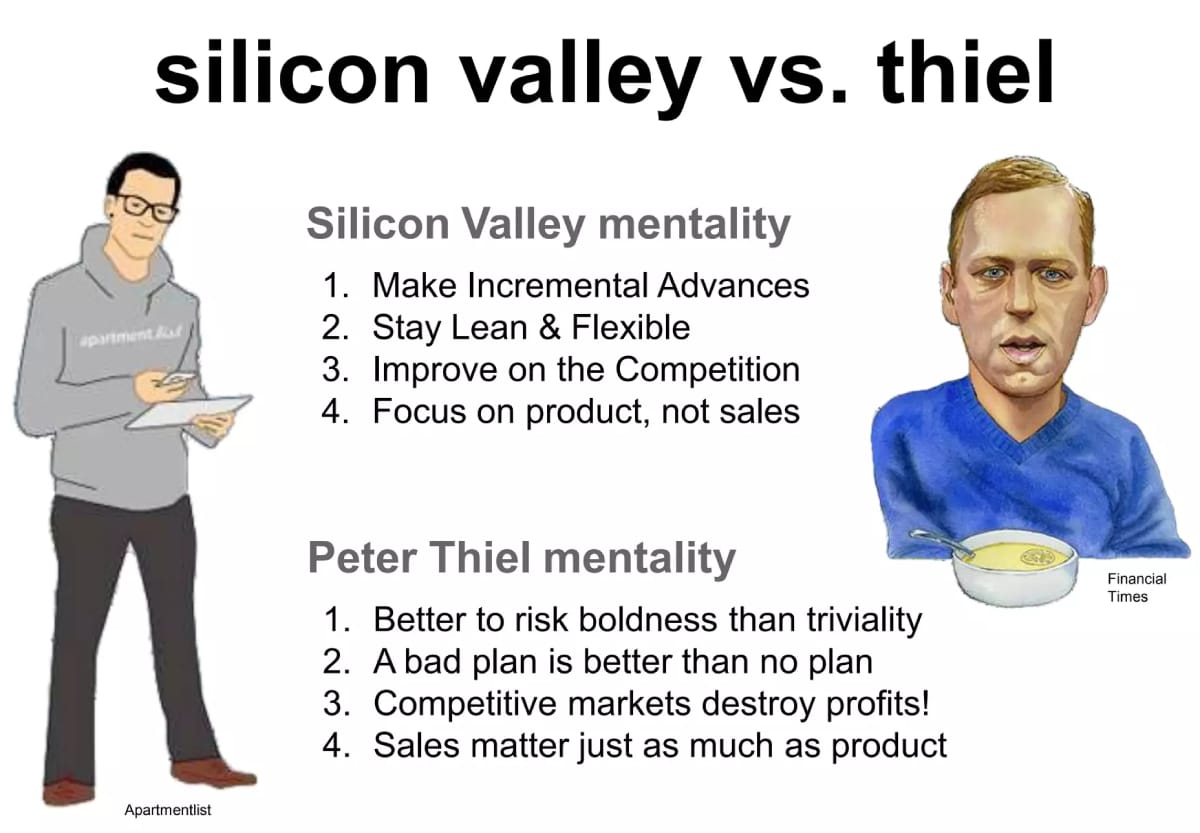

There are two kinds of innovation.

The 0-1 type of innovation as popularized by Peter Thiel is revolutionary. It’s the novel kind of innovation that permeates across the entire economy which facilitates new derivative technology/ business models.

The 1-N to innovation is evolutionary. They are continuous improvements rather than ‘discontinuous leaps into existence;.

China has mastered 1-N innovation.

Prof Jin elaborates,

The Chinese are particularly good at making existing technology both better and cheaper. Huawei’s top-end handset is half the cost of an iPhone, while Xiaomi’s equally sleek smartphone costs even less. Xiaomi was ranked number one as a global smartphone brand in 2021. The Chinese manufacturing process itself is swift, agile, and lean, making it possible to produce high-quality goods at a fraction of the cost typically incurred in other countries, even before factoring in the cost of labor. Using modular manufacturing technologies, for example, Chinese companies can build a sixty-story hotel in less than three weeks.

Copycats and Forced Tech Transfers

Two common arguments against China’s innovationare worth exploring further.

First, China is a copycat.

That has been true during China’s rapid ascent in the first 40 years.

But, as my friend, Shaun Rein pointed out to me once, a huge reason companies and consumers indulged in pirated goods in the past was that they were poor and couldn’t afford the real thing.

But once, they could afford the ‘real deal’, they switch over instantaneously.

Weirdly, piracy is a form of free marketing/ brand building.

(It’s also why LVMH is currently crushing the Chinese luxury market; and Disney’s theme parks in China are so popular today.)

Prof Jin adds to the conversation,

It's also important to bear in mind that all economic success stories include a stage that involved copying and mimicking the technologies and products of industry leaders. Imitation is a basic aspect of nature and of economic life. No one would argue, however, that stealing British designs for looms and mills made America an economic superpower, or that copying turned Japanese companies such as Nintendo, Hitachi, and Sony into household names worldwide. No economy copies its way to the top. And today we see the imitation phenomenon starting to run in a new cycle; now it is Chinese companies that are being copied, this time by their Malaysian, Indian, and Philippine competitors.

Second, China adopts forced technology transfer.

When foreign companies want to operate in China to benefit from its lower costs and large market, they must establish joint ventures with Chinese firms. This often involves the sharing of proprietary technology. In essence - its a quid pro quo deal of ‘trading markets for technology.’

This is not a Faustian bargain for two reasons:

- Foreign companies take the deal because they believe the revenue generated from access to the burgeoning Chinese market will enable them to reinvest into their R&D more aggressively.

- Foreign companies can keep their core technology at home and share only the technology necessary for their China market. After all, China was still a developing market, and the demand for their products was often lower in technological sophistication.

As China becomes the leader in many novel areas of technology, the pendulum of technology transfers has begun to swing the other way.

This is particularly true for green innovation. As author Scott Malcomson observed in an article in Foreign Affairs, Ford and Toyota invested in Chinese EV companies so that their technologies could be brought to the American, Japanese, and European markets.

China Going Zero To One

Ultimately, quantum leaps emerge from basic research—a deep, broad knowledge base acquired without a specific commercial purpose or aim. It expands through collaboration between universities, national labs, and industry to produce and share knowledge in an environment that fosters learning, curiosity, and exploration. Despite its recent efforts to catch up, China has fallen way behind in this regard, partly because its universities and research centers have historically placed an outsized emphasis on quantity—focusing on the number of academic publications and patents, for example, rather than their quality.

The follow-up question you have to ask is why?

Why the obsession with volume?

China has a ‘youthful national psyche’ that wants to sprint to success.

Start-ups become billion-dollar companies within just a few years, high-speed train stations are built in a matter of months, academics are pushed to publish frequently in prestigious journals, and the Chinese government trades access to its markets for foreign technology that fills specific gaps. These are all signs of a nation eager for instant results, quick fixes, and overnight wins.

But, for revolutionary innovation to take root, a country must play the long game.

Its leaders must cultivate the soil that allows a freer exchange of information, a well-functioning ecosystem that has the right kinds of incentives:

Universities pursue the advancement of knowledge for its own sake, firms innovate and invest in emerging technologies, and the state plays a supporting role without imposing itself in ways that squelch innovation. Strong intellectual property protection provides additional incentives to come up with new inventions, and market forces contribute their process of “creative destruction.

The US got this fundamentally right.

Here’s an example: Why do we take US VCs as the global standard of VCs?

The reasons is because they actually venture out.

They invest in nascent technologies, ‘oddballs’, and high-risk startups, knowing full well their investments may evaporate.

But they do it.

(It's worth remembering Jack Ma got his start because it was US investors who believed in him)

The Impact of China on Globalization

Singapore went from the third world to first, thanks to globalisation.

LKY was wise enough to keep our economy open and plug ourselves directly into global trade flows.

But, for China, its impact on globalization was far bigger than globalisation’s impact on China.

After Deng’s reforms,

In less than ten years, China would become the largest exporter in the world, as Chinese manufacturers churned out a wide range of consumer goods, including clothes, sneakers, furniture, and toys, at prices more affordable than ever before. It would become the largest trading partner to more than 120 countries in 2020, taking over the role played by the US two decades prior

Since opening up. the substantial growth of Chinese weight on global economy has been nothing short of unprecedented.

After joining the WTO in 2001, China’s share of global GDP more than doubled by 2020, rising from 7.8 percent to almost 19 percent

Despite its weaker economic outlook in 2024, on a PPP-adjusted basis, China still accounts for around 19-20% of the global economy this year.

Trump’s Tariffs

President Trump loves the word - tariffs.

That’s because it’s an extremely useful tool to showcase his politics - he is an economic nationalist. (After all, he was a beloved showman in 2000s primetime TV)

He wants to protect American industries and bring more jobs back to America. Tariffs add the much-needed exclamation mark.

But, in the day and age of the global value chain, where production processes are “sliced up” and spread out- tariffs will probably hurt American industries more than help.

That’s because they sourced most of their

Intermediate products in China. Higher tariffs on these inputs meant that American firms faced higher production costs, which then squeezed their profits and forced them to lay off workers or raise prices or both.

After equipment maker Caterpillar had to pay higher duties on Chinese intermediate goods that increased its production costs by more than $100 million, it had to raise prices on the machinery it produced—a cost hike that eventually hit the pockets of American consumers. And the effect on prices didn’t end there.

Firms in the same industry jumped on the bandwagon and hiked prices even if they were unaffected by Chinese tariffs. A study by economists at the University of Chicago found that a 20 percent tariff on washing machines resulted in a 12 percent increase in the cost for US consumers.

With his upcoming presidency, tariffs will continue to go up.

Will it make for good economics?

I don’t think so.

The New Playbook

China thrives when there is social stability (i.e citizens are generally happy with their rulers and feel like they are being taken care of.)

In ancient times, it was called the Mandate of Heaven.

Today, it is akin to a moral mandate that manifests itself in the cultural zeitgeist.

What are the next steps for China?

Of the four, the following two fascinate me.

First, it is to avoid the largely unequal income distribution in many advanced economies.

China seeks an olive-shaped income distribution for its people, ample in the middle and narrow at the extremes. It prefers to have its political leaders calling the tune that corporations dance to, rather than the other way around, which has inspired regulatory action against tech platform companies and put pressure on rich entrepreneurs.

President Xi’s Common Prosperity vision best articulates this.

In the US, there has been clamours for greater regulation in big tech from the past decade but so far, we have not seen anything meaningful materialize.

Here’s an example.

Meta was fined 800m euros a month ago for flouting EU regulations. That was 2% of their Q3 revenue. In other words, the court took two days of Meta’s earnings. Crackdowns from the Western world are usually just a slap on the wrist.

Conversely, in China, when the government says they are cracking down.

You can hear the crack from Singapore.

(I am not making a moral judgement, but I think it's equal parts scary and impressive how serious the Chinese government are in regulating their tech companies when they want to.)

Second, China will need to mature and build lasting institutions.

For society as a whole, process becomes as important as outcomes. The means must be justified on their own merits, not simply by the ends. China is maturing, and that maturation will accelerate as the state evolves along with its people in an ongoing dynamic, increasingly shaped by a new generation.

Deng famously said, “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.”

Now, the Chinese care about whether the cat caught the mouse properly.

Institutions will become increasingly important to ensure that competition will be fair.

Reading this reminded me once again that LKY was a far-sighted leader.

He knew his charisma had a shelf-life and that Singapore needed strong institutions to thrive as a small city-state.

The moment he got our economy going, he started building Ministries and statutory boards—bureaucracies that would ensure Singapore’s development would not be haphazard.

On a final note, what I love about this book is its tone.

Throughout the entire book, you can feel how optimistic Prof Jin is.

It reminds us that no matter where we come from, we have much more in common than we realise. "For one, we all want a brighter future for our children."

But to make that possible, our nations will have to adapt to and harmonize with new realities—together.